Confronting Racism: A Public Health Crisis

The COVID-19 pandemic has highlighted preexisting economic, social, and health inequities in the United States and has exposed the nation’s deficient public health and health care infrastructure. Recent data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention show that Black Americans are nearly three times more likely to be hospitalized from COVID-19 and close to twice as likely to die from COVID-19 than non-Hispanic white Americans.[i]

Racism and its manifestations within our institutions is a fundamental cause of racial and ethnic health inequities. Dr. Camara Phyllis Jones, a former American Public Health Association president, defines racism as:

A system of structuring opportunity and assigning value based on the social interpretation of how one looks (which is what people call race) that unfairly disadvantages some individuals and communities, unfairly advantages other individuals and communities, and saps the strength of the whole society through the waste of human resources.[ii]

To be a healthier country and to reach health equity, it is important that we name racism as a root cause of increased morbidity and mortality among Black people and develop solutions that target and dismantle racism within systems of power.

Social Drivers of Health

In the United States, social stratification based on race disproportionately structures access to health protective resources like stable housing, employment, healthy foods, and medical care. Racism created vulnerabilities in Black and other racial and ethnic minoritized communities well before the COVID-19 pandemic. The legacy of historically racist policies combined with current, more covert forms of racism have created conditions for poor health outcomes among Black populations.

Housing and Neighborhood Quality

- The conditions in which we live have the greatest impact on our health outcomes. Black people are more likely to be poor, given the country’s racialized economic system, and many of our neighborhoods are under-resourced. The places we call home have limited access to affordable and healthy foods, are far from primary care facilities for prevention and chronic disease management, and lack safe streets and green spaces for physical activity and general wellbeing. The absence of critical resources and services in Black communities is a direct result of redlining, segregation, gentrification, and other discriminatory policies and practices that intentionally strip resources from Black people and our neighborhoods. The conditions of these neighborhoods contribute to increased stress and poorer, chronic health outcomes, leading to increased risk for COVID-19 susceptibility, severity, and mortality.

Economic Security

- Black, Indigenous, and poor people disproportionately make up the working class because the economic system of the United States is built off racial capitalism. During the pandemic and subsequent economic shutdown, we were overrepresented in low-wage jobs that were newly deemed essential, putting us at greater risk of infection. Black people were also more vulnerable to job loss, which increased our susceptibility to a multitude of social and economic risk factors. Often, when people have to choose between paying for medical services or putting food on the table, medical treatment gets de-prioritized.

Access to Quality Health Care

- Health care utilization has been traditionally lower among Black Americans than other racial and ethnic groups. This is due in part to structural barriers to accessible health care and, in part, due to the historical and current reality of US medical institutions acting as agents of violence against Black bodies. For example, during segregation, Black people were treated in separate, underfunded, and understaffed facilities. We remember the Tuskegee Study of Untreated Syphilis in the Negro Male and the theft of Henrietta Lacks’ cells. This violence continues today. We are bombarded with a steady stream of stories about Black birthing people not being listened to or Black patients being refused pain management. Medical systems have been structures of oppression for Black people for centuries, resulting in inaccessible, poor quality, and untrustworthy care.

New Paths Forward

To move towards a more equitable future, we must interrogate and dismantle the racist structures that lead to vulnerability and invest in the creation of strategies that seek justice and center the voices and experiences of marginalized peoples.

Community Based Health

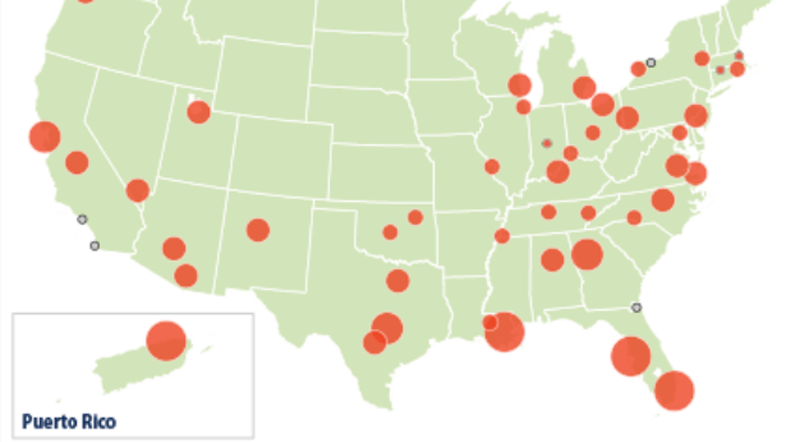

- People want to receive care in trusted places where they feel safe. Black people should establish our own spaces to educate ourselves on preventive health and provide vital resources and services in our neighborhoods. We can take lessons from the community organizers of our past. The Black Panther Party established community clinics in 13 cities across the country to provide health education, mobilize resources to mitigate diseases and other chronic illnesses, and provide housing assistance and legal aid. Community-based health care is an effective model to provide culturally responsive care in communities where economic, political, and social barriers prevent people from accessing quality services. The clinics that the Panthers ran were critical in the fight to overcome the structural racism and economic inequality that prevented many Black people from going to hospitals and other care facilities.

Training of Health Care Professionals

- Medical schools and training centers must be more intentional about naming racism as a cause of health inequity, and they must develop curriculums to teach this. Medical schools still use race to pathologize racial and ethnic minoritized patients. For example, medical students are taught that being Black is a risk factor for a varied number of medical conditions. In reality, racism is why Black people face a disproportionate burden of illness. To transform how medical care is delivered, educators must recognize that medical instruction is biased and must be reevaluated using an anti-racist lens. Frameworks such as Critical Race Theory and the social determinants of health can be used to advance students’ understanding of the fundamental causes of health inequities.

Equitable, Tech-Enabled Care

- As technology plays a larger role in care both in and out of medical spaces, it is essential that these solutions — such as machine learning, big data, and virtual engagement— are designed with empathy for marginalized groups who are most vulnerable. Often, these tools mirror the racialized biases of their creators and our society. During the pandemic, we saw a huge shift to telemedicine that allowed doctors to provide care to patients from the safe distance of their homes. But this benefit also has the potential to build further barriers to health-promoting services due to our nation’s racialized digital divide. If we are going to create new tech-enabled models for servicing patients, we need to ensure that they improve health outcomes for those in the greatest need. Otherwise, these technologies will simply reflect the biases that currently infect and infest our systems. We must prioritize developing tools in an anti-racist way.

COVID-19 is not, as some early commentators claimed: “the great equalizer.” Yes, we were all vulnerable to infection, but Black people and other marginalized groups were uniquely predisposed to carrying a greater burden of sickness and death. We must be intentional about targeting racism as the root cause of inequities across systems of power — including the medical industrial complex. We must mobilize our own resources to create the tools and resources that can protect us from a system designed to kill us.

[i] Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. “COVID-19 Hospitalization and Death by Race/Ethnicity.” National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases. Last Modified 23 Apr 2021. Retrieved from: https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/covid-data/investigations-discovery/hospitalization-death-by-race-ethnicity.html

[ii] Jones CP. Levels of Racism: American Journal of Public Health. 2000

A Climate In Crisis

A Climate In Crisis

Executive Summary

Executive Summary