The New Normal: How Canceling Student Debt Can Create a More Equitable Society

|

|

Federal Advocacy Director & Senior Policy Counsel, Center for Responsible Lending

|

|

|

Interim President, Leadership Conference on Civil and Human Rights & Leadership Conference Education Fund; Principal, Wade J. Henderson, LLC

|

Access to higher education is a longstanding civil rights issue. In the past, the exclusion of students of color from college campuses was accepted as standard operating practice — or even legally sanctioned. While students of color are no longer legally excluded from campuses, today financial exclusion prevents them from attaining a college degree and realizing its benefits.

Just as the COVID-19 crisis shed a bright light on stark inequities in our health care system and disparities in how we experience and navigate economic disruption, that same penetrating light has exposed the longstanding impact of student loan debt on millions of people’s lives and our nation’s economy. Americans owe a collective $1.7 trillion in student loan debt, ranking second only to mortgage debt. This massive burden is borne disproportionately by communities of color.

As we begin to build our new normal, canceling student debt and fixing our broken higher education system is essential. We must reject the notion that attaining a college degree must equal a lifetime of debt. We must reaffirm our commitment to higher education access and make it a reality. This starts by unburdening the millions of families impacted by the student debt crisis, and then actively working to fix our higher education system, which will move us toward closing the racial wealth gap.

Federal policies created this crisis; federal policies must solve it. President Biden should relieve borrowers and taxpayers of this unsustainable balance through substantial broad-based cancellation.

President Johnson signed the Higher Education Act in 1965. The law — enacted to open the doors of higher education to low- and middle-income students, students of color, and women through need-based grants, work study, and federal student loans — was designed to expand access to college to all Americans. While the GI Bill and the National Defense Student Loan program had previously opened access for some, the HEA marked a new major public investment in higher education intended to help more students attend and pay for college. But not all students benefited equally from these public investments. Segregation, discrimination and the long history of resistance to integration at public institutions denied Black students full access to both the GI Bill and the benefits of the Higher Education Act.

In the following decades, legal exclusion quickly morphed into financial exclusion. In fact, at the very moment when college campuses were beginning to diversify, policymakers began shifting the costs of higher education from the public to the individual student. Today, while Pell Grants remain the largest source of federally funded financial aid for higher education, they do not cover anything close to the real cost of college. State higher education budgets have never recovered from the drastic cuts made in the wake of the Great Recession, and income and wages have remained stagnant. Given this context, more families are forced to rely on increasing levels of debt to pursue postsecondary education.

This shift in financial responsibility compounds what is already a difficult situation for Black and Latino students struggling to fund their college experiences. The ongoing legacy of systemic racism and exclusion and diminishing public (and private) investment in HBCUs and other minority serving institutions have left students of color in a worse state, making them especially vulnerable to being preyed upon by poor-quality for-profit institutions that fail to provide reliable educational benefits. For-profit institutions target students of color (41% of students enrolled at these colleges are Black or Latino), women, and veterans. While these institutions thrived under the previous administration — benefitting from the rollback and gutting of common sense rules of accountability — many students ended up with unmanageable debt, a low-quality degree (or no degree at all), and poor employment prospects.

Put simply, once considered “the great equalizer,” college and college degrees have failed to live up to their promise for too many Black students and graduates. Rather than helping communities of color build wealth, recent research shows that a college education actually deepens the wealth gap due to the already high cost of living and existing structural disparities in our society and economy.

But despite the wealth depleting effect of higher education, especially for students of color, the pursuit of higher education is not a choice. In today’s workforce, a postsecondary degree is a necessity, not a luxury. Students of color are often presented with two “options”: Get a college education and accrue a high amount of debt or forego college and limit their chances of finding decent paying jobs.

Student debt has delayed, disrupted, and denied millions of young people the milestones many of us have taken for granted, including the ability to purchase a home, start a business, have children, save for retirement, get married, and more. Further, Black families have just a tenth of the wealth of white families and Latino families have just an eighth. These existing wealth disparities make the student loan debt burden particularly heavy for African American and Latino communities. Historical and ongoing racial discrimination translates to higher loan amounts for the same degree, discrimination in the labor market, inadequate funding for institutions that serve higher numbers of students of color, and other structural disadvantages.

Further, white college graduates are significantly more likely to receive financial support from their parents for their education. While 32% of white parents contribute large financial gifts of $10,000 or more, only 9% of Black college-educated households can do the same. Even when Black students received some family support for higher education, the amount averaged to just over $16,000, versus the nearly $73,500 white students receive on average.

Meanwhile, almost three times as many college-educated Black households are providing economic support to their parents as white college graduates. As they support their parents, many Black households are also working to provide postsecondary educational opportunity to their children, further compounding their debt burden. Thus, for many Black families, pursuing higher education now means being trapped in an intergenerational cycle of debt.

As a result, students of color end up needing to borrow more, and a disproportionate percentage of them (including the majority of Black students) will experience delinquency and default on their student loans. And because women also shoulder an excessive amount of the student loan balance, they are also more likely to have difficulty with repayment, with Black women bearing the brunt of this load.

Because Black borrowers disproportionately struggle with student debt at every income bracket and education level, all policy solutions, including cancellation, must center equity and consider wealth, not income.

While we support reforming the repayment system, that alone won’t fix this. After 20 years in repayment, the typical Black borrower still owes 95% of their original balance while their white peers owe only 6%. And, as noted, Black borrowers are also more likely to fall behind on their loans and are more likely to face the extremely harsh repercussions of defaulting on a federal student loan. The balances also sit on their household finance sheet and their credit reports, impacting not just their financial security but their mental health as well.

The only effective solution to addressing the student debt crisis begins with debt cancellation.

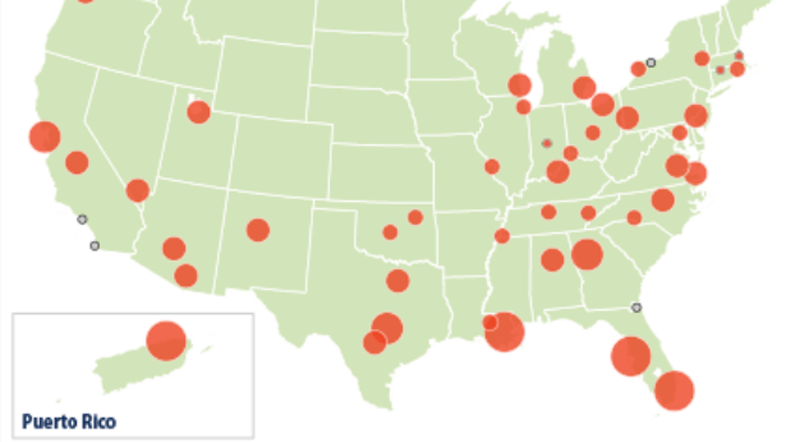

According to federal data released in April, canceling $50,000 per borrower would have a significant impact on those devastated by student loan debt; 36 million of the 45 million federal student loan borrowers would have their debt eliminated. That includes 9.8 million of the 10.3 million federal student loan borrowers who were in default for more than three months at the end of 2019. It also includes more than 4 million people who have been in repayment for more than 20 years.

After cancellation, the next necessary step is to clear the books of the remaining bad debts held by borrowers who have been in repayment for more than 15 years. Students and families shouldn’t have to live under the weight of student loans for decades, as under the current system. Debts should also be cleared for other borrowers who will continue to struggle in repayment, such as those whose debts have been in default for three or more years and borrowers receiving federal means-tested benefits for three or more years. This step would benefit borrowers, the economy, and the federal government.

Beyond cancellation, our “new normal” will require other policies that expand meaningful higher education access to communities of color: Doubling the Pell Grant, debt-free college, income-based repayment reform, full and equitable investments in HBCUs, and accountability for predatory for-profit institutions are also necessary to build a better, more equitable higher education system.

America is at a social and economic justice crossroads. Our nation is wrestling with its legacy of structural inequity while struggling to achieve economic opportunity for all. As a society, we can choose to reset; we can choose to codify and prioritize justice and equity.

It is past time for a new higher education social contract, a contract that embodies the ideals of civil rights leaders, including the National Urban League’s own Whitney Young. And the very same ideals that President Lyndon B. Johnson laid out more than 60 years ago.

A Climate In Crisis

A Climate In Crisis

Executive Summary

Executive Summary